We've all found ourselves getting "in the zone" when we work. We lose track of time until "just a couple of hours" becomes all day. Whats happening to you isn't entirely some superhuman ultra focus, enabling you to ignore everything short of the urge to pee (and sometimes even that). What is happening is that you are entering a mental state of operation known as flow.

Flow is a mental state in which the individual transcends conscious thought reaching a heightened state of both concentration and calmness. It is characterized by energized focus, full involvement, effortlessness, and enjoyment in the process of whatever activity you are doing. In essence it is the complete absorption into what one does.

Being able to enter a flow state usually means that you are doing

something that you enjoy and are good at, but that also challenges you.

Achieving this requires a confidence in skill that matches the task at

hand. I believe that if you know enough about what you are doing, and

you have the confidence and skill level to do what you do without

thinking about it at every single turn, you can allow your mind to let

go enough to reach your state of flow.

When in a flow state you are practically immune to any internal or external pressures and distractions that might otherwise hinder your performance. You simply stop thinking about any other problems you might have and concentrate solely on the task at hand. In this way, achieving a flow state can become your very own version of therapy or a meditation of sorts.

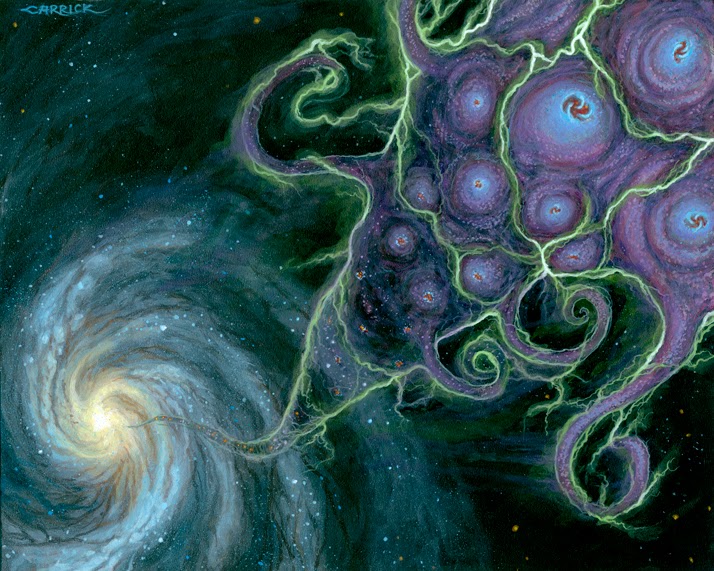

Below is a detail from a painting I did back in 2011. It was part of my thesis show in college and I was very strapped for time. This resulted in very very late nights and long long days of painting. For this particular piece I found myself so tired that I would doze off mid brushstroke, waking up periodically to find that I'd slashed green or red across the whole face, forced to start again from scratch. I can't remember much of the painting process but after dozing in and out of not quite sleep countless times the last thing I remember was waking up (or rather becoming aware) at my easel to the completely finished face shown below.

I like to think of it as exaggerated proof that a flow state is the ultimate creative zone and that being in one is to be at the highest level of focus towards a particular task that you can be. To be so immersed in the task at hand that your brain can actually do it in it's sleep.

.jpg)