|

| The Nation Makers by Howard Pyle |

Friday, July 4, 2014

Tuesday, July 1, 2014

When to Walk Away...

As an artist there are three situations where you really need to learn to walk away...

1. If there is an opportunity to work on a project that won't help you get better, or advance yourself as an artist (particularly in the field in which you want to be creating art), say no and walk away.

Money is a tempting thing in this world and I, like many of you out there, have taken on projects solely for the promise of getting paid. These were all projects in different niches of art, illustration, and in some cases graphic design that I had very little interest in other than the fact that there was a paycheck at the end of it (and in some cases not even that). When I look back on those projects I can take very little away from them that helped to make me better at what I want to do; not one of them sticks around as a piece to advance my career and at this point in my life, to be completely frank, they feel like time ill spent.

2. If you've been working for more than 4 hours straight you need to walk away, albeit briefly. Take breaks often when you are working. Not so often that you lose your flow, but often enough that you can come back to the easel with a fresh eye now and again. Even more so if you are having trouble with a particular passage; walk away and leave it for a while. Go take a walk and look back at it later. Work on something else. Either way let your mind work on the problem while you focus your efforts on other things. The next time you're back at the painting, or working that particular passage, it might be a no-brainer. The answer may have been there all along and you just weren't in the right state of mind to see it.

3. When your painting says all it needs to say; when you have sufficiently told the story; when everything is finally done... walk away.

This is easier said than done.

It often feels that art is never really finished; given the opportunity an artist might work and rework a piece forever. Second guessing themselves and changing things. Tweaking things. Sometimes the best thing to do in this case is just walk away. Call it finished for now. Look back at it in a few days and see if you're still seeing the same stuff, the same problems.

|

| Frank Frazetta's Conan the Buccaneer upon publication |

Unless there are hard deadlines involved you always have the freedom to go back and change things. Even after deadlines or print dates, you can always rework your painting for yourself.

|

| Frank Frazetta's Conan the Destroyer, reworked after publication |

Tuesday, June 17, 2014

Zorn Limited Palette

My early experiences with color in school always left me feeling a little unfulfilled. Like I was always using the wrong tube colors for the effect I wanted. I needed to find a starting point. Those basic colors with which to paint that would give me what I wanted...

Anders Zorn used a limited color palette almost exclusively. The tube colors of which I have seen vary depending on where your information is coming from. In any case the essence of the palette remains constant.

White

Ivory Black

Yellow Ochre

Red

Ivory Black

Yellow Ochre

Red

The whites have ranged from Flake to Titanium, Flake being the more traditional choice.

Ivory Black is the standard, however I have seen this subdivided into warm and cool black mixtures.

Yellow Ochre remains unchanged.

Red was traditionally Vermillion but Cadmium Red is the adopted standard. I have seen the reds vary between Cadmium Red Light, Cadmium Red Medium, and Cadmium Scarlet.

This is a great starting palette for figurative painting. It may seem basic at first but with a strong understanding of color theory you can get a surprisingly wide range of colors from this strictly limited palette.

Tuesday, June 10, 2014

Crossroads

As an artist you face infinite possibilities when it comes to creating your art. These possibilities can be limited by a number of things; content, intent, style, material, all of which may already be set and some that may not be. Either way, when you encounter a situation where you can go left or right. Just go. Make a decision and proceed.

In other words...

"When you come to a fork in the road, take it" -Yogi Berra

Donato Giancola had a great post about this over on Muddy Colors, you can read it here.

Tuesday, April 22, 2014

Cheating

There have been a few blog posts over on Muddy Colors in the past couple of days on the subject of "cheating" in art with the use of photography and/or digital media.

This term "cheating" comes up frequently with digital media in regards to images that either use photo reference, photo collage, photo paint overs, or even just straight hyper realistic painting. Often people will accuse the artist of "cheating" because they may have used shortcuts to get where they ended up with the final. The truth of the matter is that when it comes to image creation and process there is no such thing as "cheating". Any means you use to get to a final image is fair game. However, since some of these processes may include the heavy use of photos it would be up to the artist personally to determine whether the use of these photos is to them "cheating".

An example of this would be an artist who uses a combination of photo collage and paint overs. If this artist poses his own models, takes his own pictures from those models, edits those photos and collages/paints over them then that artist can feel fulfilled in that he truly created his image from start to finish without cheating. Conversely, that same artist could use images they found online or from a magazine, collage and then paint over those images and feel like they cheated to get to the final, even though they may have extensively altered or painted into/over those photos. In this case it is up to the artist whether or not they cheated by using images they found rather than images they created (not to mention addressing copyright issues with found images and whether or not it is legal to use certain images within your work).

This is where the artist needs to take a step back to see if they are cheating themselves in the creation of their art. For instance, if you think that posing your own models or sketching from life would have gotten you to a better quality final than having found reference elsewhere, then I would say that you were cheating yourself to some degree.

This is the only 'cheating' that I think really makes a difference to an artist and only in so far as they are concerned about their own process and how they got to the final image (which is what really matters).

Wednesday, March 26, 2014

Underpainting

In painting one should always have their eye on the final layer.

Everything you do from the very first thumbnail should be to facilitate the final piece. The end goal. That perfect image you had in mind from the very first time you put pencil to paper.

Unfortunately it doesn't always work out that way. For instance, you might find yourself laboring away at your work for hours, days, weeks, or dare I say months ending up nowhere near where you started but still not any closer to finish. Needless to say we all stray from our planned path at times but that doesn't mean we won't end up exactly where we need to be in the end. Sometimes it requires a simple course correct and sometimes you've just got to wade through the mud. Either way, everything you put down is just the underpainting for what comes next.

The underpainting is your foundation. It will inform every decision you make throughout the process. It is where you can make your mistakes, take risks, or just play around.

Even when you look back at what you did and say... "nope, should of done this instead. This would have gotten me there quicker"... realize that you had to make those mistakes and take those risks to have found that out.

Could it have been easier? Yes, and you know that now.

So when you work and you work and all you can see is the underpainting, just know that it's all building up to the finish. In the end it will only make your painting that much richer, that much more involved; and you can always look forward to the moments where your earliest underpainting still shines through. Those moments where you know you got it right in the first pass, where you took a big risk and it just worked. The moments that stood up to all the scrutiny that everything else didn't, because even finished isn't really finished sometimes.

Everything you do from the very first thumbnail should be to facilitate the final piece. The end goal. That perfect image you had in mind from the very first time you put pencil to paper.

Unfortunately it doesn't always work out that way. For instance, you might find yourself laboring away at your work for hours, days, weeks, or dare I say months ending up nowhere near where you started but still not any closer to finish. Needless to say we all stray from our planned path at times but that doesn't mean we won't end up exactly where we need to be in the end. Sometimes it requires a simple course correct and sometimes you've just got to wade through the mud. Either way, everything you put down is just the underpainting for what comes next.

The underpainting is your foundation. It will inform every decision you make throughout the process. It is where you can make your mistakes, take risks, or just play around.

Even when you look back at what you did and say... "nope, should of done this instead. This would have gotten me there quicker"... realize that you had to make those mistakes and take those risks to have found that out.

Could it have been easier? Yes, and you know that now.

So when you work and you work and all you can see is the underpainting, just know that it's all building up to the finish. In the end it will only make your painting that much richer, that much more involved; and you can always look forward to the moments where your earliest underpainting still shines through. Those moments where you know you got it right in the first pass, where you took a big risk and it just worked. The moments that stood up to all the scrutiny that everything else didn't, because even finished isn't really finished sometimes.

Thursday, March 20, 2014

What to Listen to...?

I know I'm not alone in the fact that I need to be listening to something while I work. This of course raises the question "what to listen to...?"

For me it is frequently changing and is usually dependent on my tastes for the week. I've gone from music to audiobooks and back but every so often I like to throw in the occasional podcast. There are hundreds of podcasts out there but today I want to direct you guys to one in particular.

SiDEBAR is a comics, art and pop culture podcast that can be found here. This podcast is just fantastic. It's hosted by some great guys and they've had some fantastic guests. Everyone involved is very down to earth and they all just love to talk about ART. I've heard some amazing stories from these interviews and picked up some great tips on the illustration business and on life as an artist in general.

They have an extensive archive (the BARchives) and all of their shows can be found there. I strongly recommend that you go browse and listen to some.

Below are just a couple (several) of my favorites...

George Pratt (part 1)

George Pratt (part 2)

Greg Manchess

Iain McCaig

Brom

James Remar

Drew Struzan

Irene Gallo

James Gurney

Phil Hale

John Van Fleet

Jeff Preston

Justin 'Coro' Kaufman

Brad Rigney

For me it is frequently changing and is usually dependent on my tastes for the week. I've gone from music to audiobooks and back but every so often I like to throw in the occasional podcast. There are hundreds of podcasts out there but today I want to direct you guys to one in particular.

SiDEBAR is a comics, art and pop culture podcast that can be found here. This podcast is just fantastic. It's hosted by some great guys and they've had some fantastic guests. Everyone involved is very down to earth and they all just love to talk about ART. I've heard some amazing stories from these interviews and picked up some great tips on the illustration business and on life as an artist in general.

They have an extensive archive (the BARchives) and all of their shows can be found there. I strongly recommend that you go browse and listen to some.

Below are just a couple (several) of my favorites...

George Pratt (part 1)

George Pratt (part 2)

Greg Manchess

Iain McCaig

Brom

James Remar

Drew Struzan

Irene Gallo

James Gurney

Phil Hale

John Van Fleet

Jeff Preston

Justin 'Coro' Kaufman

Brad Rigney

Labels:

Brad Rigney,

Brom,

Coro,

Drew Struzan,

George Pratt,

Greg Manchess,

Iain McCaig,

Inspiration,

Irene Gallo,

James Gurney,

James Remar,

Jeff Preston,

John Van Fleet,

Phil Hale,

Podcast,

SiDEBAR

Wednesday, March 5, 2014

In the Zone - Achieving your Flow

We've all found ourselves getting "in the zone" when we work. We lose track of time until "just a couple of hours" becomes all day. Whats happening to you isn't entirely some superhuman ultra focus, enabling you to ignore everything short of the urge to pee (and sometimes even that). What is happening is that you are entering a mental state of operation known as flow.

Flow is a mental state in which the individual transcends conscious thought reaching a heightened state of both concentration and calmness. It is characterized by energized focus, full involvement, effortlessness, and enjoyment in the process of whatever activity you are doing. In essence it is the complete absorption into what one does.

Being able to enter a flow state usually means that you are doing

something that you enjoy and are good at, but that also challenges you.

Achieving this requires a confidence in skill that matches the task at

hand. I believe that if you know enough about what you are doing, and

you have the confidence and skill level to do what you do without

thinking about it at every single turn, you can allow your mind to let

go enough to reach your state of flow.

When in a flow state you are practically immune to any internal or external pressures and distractions that might otherwise hinder your performance. You simply stop thinking about any other problems you might have and concentrate solely on the task at hand. In this way, achieving a flow state can become your very own version of therapy or a meditation of sorts.

Below is a detail from a painting I did back in 2011. It was part of my thesis show in college and I was very strapped for time. This resulted in very very late nights and long long days of painting. For this particular piece I found myself so tired that I would doze off mid brushstroke, waking up periodically to find that I'd slashed green or red across the whole face, forced to start again from scratch. I can't remember much of the painting process but after dozing in and out of not quite sleep countless times the last thing I remember was waking up (or rather becoming aware) at my easel to the completely finished face shown below.

I like to think of it as exaggerated proof that a flow state is the ultimate creative zone and that being in one is to be at the highest level of focus towards a particular task that you can be. To be so immersed in the task at hand that your brain can actually do it in it's sleep.

Wednesday, February 26, 2014

The Illusion of Ease

I want to take a moment to address the illusion of ease in painting and the difficulty with which an artist obtains it.

Below is a portrait of Mrs. Hugh Hammersley by John Singer Sargent...

I am a great admirer of Sargent and the apparent ease of his brushwork but it had never occurred to me that such ease was not a gift given upon reaching some level of skill where one can call themselves master. No, this ease was achieved by fighting tooth and nail with the canvas, demolishing all work that had been done before to start anew if just the slightest detail or shift of posture was not befitting the sitter.

Sargent would often repaint the heads of his sitters dozens of times. Each one from scratch. He would not reposition features or tinker with the details of a face as this meant the initial structure was wrong and had to be redone.The head of Mrs. Hammersley above was repainted no less than 16 times.

He painted his forms as a sculptor models his, laying in the broad forms first and letting the features blossom from within. They were never a separate thing to be applied to the face, they were always integral, from the very first stroke.

No matter how long he worked on a particular piece he had no qualms about destroying everything to start fresh if it was not to his satisfaction. Below is a portrait of Lady D'Abernon. After three weeks of painting her in a white dress, Sargent scraped out the painting at what would have been the last sitting. He then repainted her in a black dress in only three.

References: I found the information in this post from the accounts of Sargent's process and methods by some of his students, Miss Heyneman and Mr. Henry Haley. A collected PDF of these compiled notes can be found on Craig Mullins' site here.

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

From Color to Sound

The following was taken from an account of a sitter being painted by John Singer Sargent in 1902:

My husband came several times to the sittings. On one occasion Mr. Sargent sent for him specially. He rode across the Park to Tite Street. He found Mr. Sargent in a depressed mood. The opals baffled him. He said he couldn't paint them. They had been a nightmare to him, he declared, throughout the painting of the portrait. That morning he was certainly in despair.

Presently he said to my husband: "Let's play a Fauré duet." They played, Mr. Sargent thumping out the bass with strong, stumpy fingers. At the conclusion Mr. Sargent jumped up briskly, went back to the portrait and with a few quick strokes, dabbed in the opals. He called to my husband to come and look: "I've done the damned thing," he laughed under his breath.

What appeared to interest him more than anything else when I arrived was to know what music I had brought with me. To turn from color to sound evidently refreshed him, and presumably the one art stimulated the other in his brain.

References: I found the information in this post from the accounts of Sargent's process and methods by some of his students, Miss Heyneman and Mr. Henry Haley. A collected PDF of these compiled notes can be found on Craig Mullins' site here.

Thursday, February 13, 2014

Faithful Portraiture

Below is an excerpt from some notes on John Singer Sargent. They have been compiled from a multitude of sources and can be found at Craig Mullins' site here.

It was a common experience for Sargent, as probably for all portrait painters, to be asked to alter some feature in a face, generally the mouth. Indeed, this happened so often that he used to define a portrait as "a likeness in which there was something wrong about the mouth." He rarely acceded, and then only when he was already convinced that it was wrong. In the case of Francis Jenkinson, the Cambridge Librarian (painting below), it was pointed out that he had omitted many lines and wrinkles which ought to be shown on the model's face. Sargent refused to make, he said, "a railway system of him."

It was a common experience for Sargent, as probably for all portrait painters, to be asked to alter some feature in a face, generally the mouth. Indeed, this happened so often that he used to define a portrait as "a likeness in which there was something wrong about the mouth." He rarely acceded, and then only when he was already convinced that it was wrong. In the case of Francis Jenkinson, the Cambridge Librarian (painting below), it was pointed out that he had omitted many lines and wrinkles which ought to be shown on the model's face. Sargent refused to make, he said, "a railway system of him."

While it is true that Sargent would almost never change his subjects features at their request he did exaggerate those features required for the most faithful likeness. In this way he certainly did not paint exactly what he saw but rather captured the essence of his sitter.

Below is the compared photograph and portrait of Coventry Patmore. The portrait having been done from life (not from the photograph) both dated to the mid 1890's.

Patmore thought very highly of Sargent having wrote of him:

“He seems to me to be the greatest, not only of living English portrait

painters, but of all English

portrait painters; and to be thus invited to sit to him for my picture

is among the most signal honours I have ever received.”

He was so impressed by the likeness that he wrote of the painting:

"It is now finished to the satisfaction, and far more than the satisfaction of every one - including the painter - who has seen it. It will be simply, as a work of art, THE painting of the Academy."

Friday, January 31, 2014

Feedback Part 3

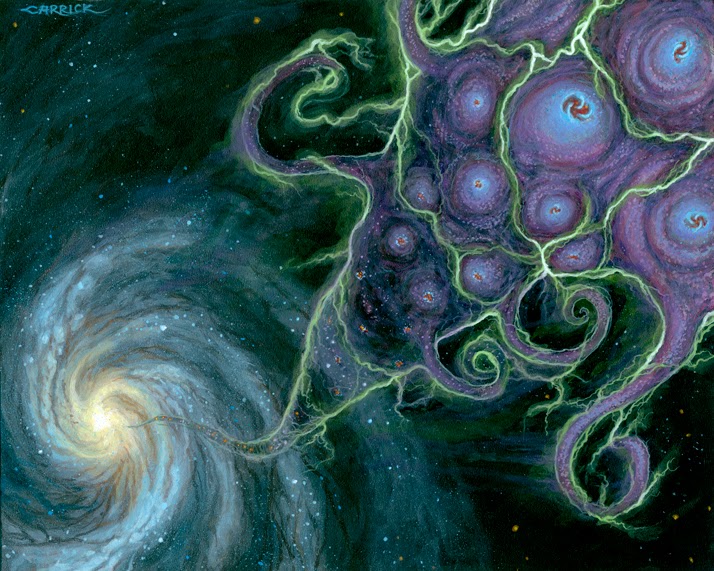

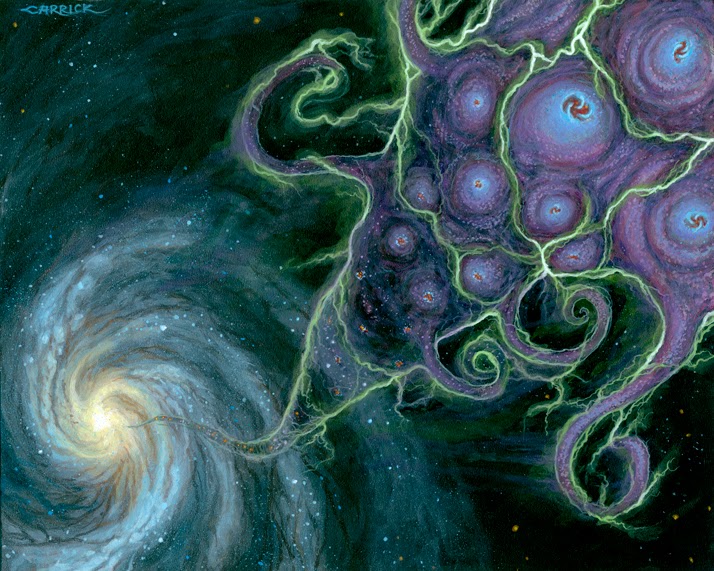

Paul Carrick came to my school as a guest lecturer during my second semester. He was there to share his experience as an illustrator with my class, to show us one of our options. It was the only thing that happened as far as my schooling went that taught me anything about illustration. In fact up to this point I wasn't even really aware of illustration being it's own field, or that you could be an illustrator.

Hearing Paul and seeing his work solidified in me what I wanted to do. I had always been interested in fantasy and science fiction. Looking at the artwork of book covers, RPG rule manuals and Magic: the Gathering trading cards had made me want to become an artist but I never realized that these people were illustrators. It seems weird to say that now but I just didn't know back then that there was a difference let alone such a dichotomy between so called 'fine art' and 'illustration'. I just thought they were all artists and that these particular artists painted fantasy or science fiction. I could get into my opinions about the break between fine art and illustration but that seems like it belongs in a future post...

Paul Carrick helped to open my eyes to illustration as a business. All of a sudden I realized that if I wanted to be a serious professional illustrator that I had to learn to make a living at it, and that it wasn't going to be easy. This was something that I wasn't going to learn in school. I immediately started to search for any book, blog, podcast or video that might help me learn, not only to draw and paint, but how to run this business I was getting into. I was determined to know all that I could about the field so I would fully understand what I was getting into.

I stayed along after Paul's lecture to talk more about the field and exchanged emails with him, asking him if I could keep in touch and send him my work every so often. This ended up being one of the best things for me. Every so often we would exchange emails and he would direct me along giving me much needed feedback. He made me realize the importance of reference, showed me where it was and wasn't working for me. He helped me with lighting and focusing the viewer's attention, using visual clues in the image to make things more or less apparent or even staged. He was always encouraging me along the way, letting me know how far I had come from when he first saw my work.

This kind of encouragement is key to a young student and indeed will be present with one's teachers and peers but it is always helpful to have the opinion of someone out in the business who isn't always nearby. An outside mentor who can lend a fresh set of eyes to your work. They may see something and say something that hasn't been said, something that perhaps you're working towards slowly but haven't yet realized for yourself. This kind of feedback can help you on your way by leaps and bounds and I am very grateful to have that with Paul Carrick.

For those of you who don't know Paul's work the link to his website can be found again HERE. He specializes in all things Lovecraft and has worked on many projects including Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu line. Below are some of my favorites...

|

| One of the original paintings he brought in that stuck with me long after he left. |

Hearing Paul and seeing his work solidified in me what I wanted to do. I had always been interested in fantasy and science fiction. Looking at the artwork of book covers, RPG rule manuals and Magic: the Gathering trading cards had made me want to become an artist but I never realized that these people were illustrators. It seems weird to say that now but I just didn't know back then that there was a difference let alone such a dichotomy between so called 'fine art' and 'illustration'. I just thought they were all artists and that these particular artists painted fantasy or science fiction. I could get into my opinions about the break between fine art and illustration but that seems like it belongs in a future post...

Paul Carrick helped to open my eyes to illustration as a business. All of a sudden I realized that if I wanted to be a serious professional illustrator that I had to learn to make a living at it, and that it wasn't going to be easy. This was something that I wasn't going to learn in school. I immediately started to search for any book, blog, podcast or video that might help me learn, not only to draw and paint, but how to run this business I was getting into. I was determined to know all that I could about the field so I would fully understand what I was getting into.

I stayed along after Paul's lecture to talk more about the field and exchanged emails with him, asking him if I could keep in touch and send him my work every so often. This ended up being one of the best things for me. Every so often we would exchange emails and he would direct me along giving me much needed feedback. He made me realize the importance of reference, showed me where it was and wasn't working for me. He helped me with lighting and focusing the viewer's attention, using visual clues in the image to make things more or less apparent or even staged. He was always encouraging me along the way, letting me know how far I had come from when he first saw my work.

This kind of encouragement is key to a young student and indeed will be present with one's teachers and peers but it is always helpful to have the opinion of someone out in the business who isn't always nearby. An outside mentor who can lend a fresh set of eyes to your work. They may see something and say something that hasn't been said, something that perhaps you're working towards slowly but haven't yet realized for yourself. This kind of feedback can help you on your way by leaps and bounds and I am very grateful to have that with Paul Carrick.

For those of you who don't know Paul's work the link to his website can be found again HERE. He specializes in all things Lovecraft and has worked on many projects including Chaosium's Call of Cthulhu line. Below are some of my favorites...

Thursday, January 30, 2014

Feedback Part 2

While they were all encouraging and they all held some bits of information that would help guide me in the coming years there was one email I received back in 2008 that would do more to influence my growth than all of the others.

It came from Todd Lockwood.

For those of you who don't know of Lockwood's work, please go check it out. He is an amazing painter and in many's eyes his is the last word when it comes to dragons.

Following are some excerpts from his email...

"Use good reference when you draw.

Drawing out of your head can be fun, but if you want to learn and draw

well, life-drawing is a must. It's an invaluable way to learn the

subtleties of the human form (something that few can ever really master

entirely), so have a regular place to draw. At home, if you have a camera, take photos from which to draw. A digital camera can be a

wondrous asset if you have access to a computer and printer. I also

strongly recommend a book called 'Drawing From the Right Side of the Brain' by Betty Edwards. It contains some amazing exercises for

stimulating the part of your brain that sees things as they really are,

and can help you break some bad habits that you have taught yourself

when you were learning the standard, over-simplified symbols of How

Things Look. Every first grader knows that a nose is an L-shape, or

upside-down 7, for example. It's not true, obviously, but even talented

artists will have set routines that they run when they are drawing an

ear, say, or an eye, that may contain inaccuracies that escape the

casual observer. The result is a face or figure that is drawn

according to a list of symbols rather than a detailed observation of

the reality, complete with light effects, shadows, perspective, and so

on. Accurate observation is essential to a good drawing. If

you always draw from your head, you will not exorcise those flawed

routines."

"Art is far more about knowing what things look like and why than it is about media, but digital media offer too many temptations that can blunt your learning ability. I recommend highly that you draw with a pencil, kneaded eraser, and a paper blending stick or stomp and concentrate on making the best black & white images that you can for now."

"There is a good resource available online: you can view the art texts of Andrew Loomis, for FREE, here: http://www.fineart.sk/photo-references/andrew-loomis-anatomy-books. Loomis

was an illustrator and teacher of art in the forties and fifties. What

most distinguishes his career is the legacy in these books. He was a

master

teacher, and covers all the basics thoroughly, with terrific

illustrations to boot. He's an amazing teacher"

He then gave me a mini lesson on light and shadow. These points as well as some others that Todd touches upon in his class at the SmART School can be found in his recent blog post on Muddy Colors here: http://muddycolors.blogspot.com/2014/01/narrative-illustration.html

LIGHT & SHADOW

"Here's

a tip for shading: light acts like ping-pong balls. A particle of light

hits a surface and bounces off at a predictable angle, like a billiard

ball banking off of a side-rail. I'm attaching some little jpegs that

demonstrate this..."

"I'm showing you two things: the light that bounces directly into your eye, as a highlight (solid lines), and the light that doesn't, which is the ambient light (dashed lines). You can think of ANY surface as a mirror which throws light back. That's easy with a flat surface, because mirrors are flat. Round surfaces are otherwise no different. Light strikes the surface and bounces off most powerfully at an IDENTICAL, but OPPOSING angle. Just like a billiard ball. So, the light bouncing toward your eye- the only light you will see, obviously- will be strongest where it is coming off of that kind of bounce. It's relative to the placement of the light source and the location of your eye, in space. A highlight IS NOT strongest where the surface is closest to the light source. It is strongest where the angle of that surface is MOST LIKELY to bounce the light straight toward your eye. That is the red lines. The ambient light is the light that is bouncing off of irregularities in the surface, and it goes in every direction. There is light bouncing everywhere, all the time. We only perceive the light that happens to be bouncing to the exact spot where our pupils are. Some of it will bounce back toward another surface, then off of that second (or third) surface and into our eyes. That's reflected light, or fill light (the solid purple line)."

There

will be a tendency for a surface to appear brighter toward the light

source, but that is different than the actual highlight. Look at the

drawing of the brick to see what I mean. There is a point of demarcation

on the corner edge of the brick where the highlight is most likely, but

the light that strikes the face of the brick as it falls away from the

light is doing so at an ever increasing angle. This will be especially

true where the light source is close. The more extreme that angle

becomes, the less likely it is that the surface irregularities will bounce some of that ambient light toward your eye, thus the light appears to "fall away".

"If

you think of a surface as a mirror, the highlight will appear wherever

that spot is that would have been a reflection of the light, were it an

actual mirror. Make sense? Some surfaces are great at reflecting, like

mirrors. Some aren't, like walls. But walls are still flat enough that

there will be a 'hot spot'. Look at the walls where you are sitting

right now and find the hot spot"

"That's all you need to know about how light works to start studying it. Everything you draw or paint is either a flat or curved surface,

and the rules will apply. Even water works that way, though

transparency is another issue. Your job as you draw is to see the light

bouncing. The better you know the volume and construction of the forms

of the objects, the better you will understand how light bounces off of

and onto those objects, so that is important too."

While I never did read Drawing From the Right Side of the Brain, the books by Andrew Loomis (especially Figure Drawing for All it's Worth) and Todd's excellent mini lesson jump started me on my quest. Thank you Todd.

UP NEXT: Paul Carrick

Wednesday, January 29, 2014

Feedback Part 1

As a young artist just getting into art school you live and die by the feedback of your teachers and peers. Some is good, but most is bad. It is up to you to weed through the endless critiques and comments to find those choice moments that strike a chord with you. This three part series will highlight some of my own choice moments. I hope some of this may resonate with you like it did with me.

After my first year of art school I was stricken by something a professor had said to me. At my final critique he asked me what it was I wanted to do after I graduated to which I replied fantasy and science fiction illustration. He asked me to look out at what the fine art seniors had done for their thesis show that year and said to me that you should just leave and go to a different school because no one is doing the type of work that interests you here.

I was a fine art major at a very small school and there really wasn't anyone doing the type of work I wanted to get into. He was absolutely right and maybe I should have taken his advice, but I stayed for a multitude of reasons, not least is the caliber of teachers I had and would come to have. I was there first and foremost to learn how to draw and paint but what he said stuck with me throughout, and in conjunction with meeting Paul Carrick (I'll get to that meeting later in this series), made me hungry for knowledge outside of my schooling.

Thank you Steve Novick for giving me that initial push to learn what I needed to learn.

My first big step came in 2008 during my first summer break. I felt that the feedback of my professors wasn't enough and that what I really needed was the opinions of the people whose work I admired and followed closely. Professionals in the field of illustration, the very people who drew me to it in the first place. I compiled a list of my favorites and sent out my portfolio in a shotgun blast of emails hoping for the best. Surprisingly enough I got several responses within the next few weeks and they were invaluable to me in my artistic growth over the next few years. To the artists both named here and not, that took time out of their day to send me these, I am extremely grateful. You encouraged and continue to encourage a young artist finding his way in this business. Below is a selection of quotes from those emails...

RANDY GALLEGOS

"Drawing is the blueprint of painting--without great drawing, color can't do its job."

After my first year of art school I was stricken by something a professor had said to me. At my final critique he asked me what it was I wanted to do after I graduated to which I replied fantasy and science fiction illustration. He asked me to look out at what the fine art seniors had done for their thesis show that year and said to me that you should just leave and go to a different school because no one is doing the type of work that interests you here.

I was a fine art major at a very small school and there really wasn't anyone doing the type of work I wanted to get into. He was absolutely right and maybe I should have taken his advice, but I stayed for a multitude of reasons, not least is the caliber of teachers I had and would come to have. I was there first and foremost to learn how to draw and paint but what he said stuck with me throughout, and in conjunction with meeting Paul Carrick (I'll get to that meeting later in this series), made me hungry for knowledge outside of my schooling.

Thank you Steve Novick for giving me that initial push to learn what I needed to learn.

My first big step came in 2008 during my first summer break. I felt that the feedback of my professors wasn't enough and that what I really needed was the opinions of the people whose work I admired and followed closely. Professionals in the field of illustration, the very people who drew me to it in the first place. I compiled a list of my favorites and sent out my portfolio in a shotgun blast of emails hoping for the best. Surprisingly enough I got several responses within the next few weeks and they were invaluable to me in my artistic growth over the next few years. To the artists both named here and not, that took time out of their day to send me these, I am extremely grateful. You encouraged and continue to encourage a young artist finding his way in this business. Below is a selection of quotes from those emails...

RANDY GALLEGOS

"Drawing is the blueprint of painting--without great drawing, color can't do its job."

"Focus your portfolio. Pick the genre of artwork you're going to focus on and do lots of that. A good

portfolio should have 8-12 pieces demonstrating different subject matter within

the same basic genre. No more, no less, and no weird, out of left field

stuff. If you want to do fantasy book covers or Magic cards, don't show

your prospective clients celebrity portraits. The reverse applies as

well, naturally. You don't send a picture of a dragon to Time Magazine

in order to score editorial art gigs. And of course, ditch the school

work. People know it when they see it, and they won't hire you if they

think you're a student or don't have professional experience. It's your

job to create the illusion that you are the consummate

professional...until you are."

"You never outgrow the need to learn. The MAIN thing is to get your

hand very much at home with the language, and the only thing for that

is gobs and gobs of practice."

"When

you paint, really concentrate on the textures and feel of the different

materials in the image. Skin, metal etc. The best way I found was to

imagine the feel of each material as you paint it. It's tricky but

you'll know when you get it. it's really like a light turning on in your

head."

"Post your work on a site like conceptart.org in their sketchbook section. You will get a lot of honest critiques

from professional and amateur artists alike. Many artists have made huge

leaps through this site. Be humble and take constructive criticism to

heart."

"In the end you just have

to practice and make each piece of work better than your last. be aware

of your weaknesses more than your strengths and work on them. Recognize

what makes other artist's images work and try and introduce it to your

compositions."

UP NEXT: Todd Lockwood gives me my first lesson on light and shadow...

UP NEXT: Todd Lockwood gives me my first lesson on light and shadow...

Friday, January 24, 2014

Style

Style is in my opinion an awful nightmare that is constantly looming over any artist who wants to "make it" in the art world. It is ever present and I am sure everyone has felt that they needed to find their own unique style or else they would surely fail before they ever really started.

As a student I wasn't so focused on it until I started to become

comfortable with my chosen medium. The more comfortable I got with the

materials it seemed the more uncomfortable I got with the result.

I spent a large part of my

time in school poring over my favorite artist's work. Reading books and

watching videos about their processes, trying to find that elusive

secret that somehow unlocked their 'style'. I

learned a great deal about their working methods and I unlocked quite a bit in

my own mind about conceptually painting but I was still no where closer

to finding their, let alone my own, style. My knowledge of painting then became so much greater than

my technical skill which was entirely backwards. I found myself painting

more in my head than on the canvas which is definitely a start, but not when one

hampers the other.

The fact is that there is

no covetous secret that anyone possesses that will suddenly let you

inherit a style, or all of a sudden develop your own.

The only real secret behind developing a personal style is hiding in plain sight...

WORK.

DRAW.

PAINT.

Just do what it is you do.

You will discover it for yourself.

Borrow from the masters. Draw from your inspirations, but make sure you draw from ALL of your inspirations. Keep what works for YOU in the way that YOU interpret it (it will never be like the source material, nor should it). Play around and invent your own methods for things but don't try too hard to achieve originality, strive instead for authenticity. Be true to what feels right for YOU.

The goal here is to see a unique style shining through your work. You may only see glimpses at a time but the more you train yourself and recognize the good from the bad from the blatant copies, you will see those glimpses more and more. The key is to keep any singular vision from outshining the rest, unless of course it is your own.

DON'T BE AFRAID OF STYLE...

Part

of one's training as an artist should be to expect, endure, and react to

change. This includes your personal style. Expect your style to change

because it will, frequently; especially in the beginning of your

education and career.

As your technical skill develops and matures, your style

will react and adapt. As in my case, I felt my conceptual knowledge

lapped my technical skill which then caused my technical skills to

develop that much faster as I put into practice the concepts I had

learned. This inherently caused the style and look of my painting and

drawing to change within a very short time. It is still changing.

This change however has to

occur naturally. The more you try to force the change early on the more you will

probably end up just copying someone else.

It

wasn't meant to be easy to find your unique voice when it comes to

style. Take your time and it will pay off in the end.

The most beautiful thing about personal style and in fact art in general is that there is never an end to this grand journey we're on. Change is inevitable, so recognize and embrace it.

The most beautiful thing about personal style and in fact art in general is that there is never an end to this grand journey we're on. Change is inevitable, so recognize and embrace it.

Friday, January 17, 2014

Better Things

Just downloaded Maria Cabardo's new film, Better Things: The Life & Choices of Jeffrey

Catherine Jones. The download at $14.95 (discounted for this month from $19.95) is a must see. DVD goes on sale in February followed by the Blu-ray with plenty of extras.

Jeffrey Jones was a force in the field of illustration and his story is fascinating. His effortless style and the almost abstract simplicity of his forms are just stunning. Check out the trailer and a sampling of work below...

Jeffrey Jones was a force in the field of illustration and his story is fascinating. His effortless style and the almost abstract simplicity of his forms are just stunning. Check out the trailer and a sampling of work below...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)